When I first started researching El Sistema, most of what I could find online was footage of the Simon Bolivar Orchestra and Gustavo Dudamel - both never cease to amaze me, but as an elementary music teacher, I wanted to know how they got there. What were these exceptional musicians doing at 5 or 10 years old in their local nucleo?

When I first started researching El Sistema, most of what I could find online was footage of the Simon Bolivar Orchestra and Gustavo Dudamel - both never cease to amaze me, but as an elementary music teacher, I wanted to know how they got there. What were these exceptional musicians doing at 5 or 10 years old in their local nucleo?After observing ten different sites throughout Venezuela this past month, I now have a better picture of what their experiences might have looked like. Rodrigo Guerrero, International Affairs Coordinator of FESNOJIV, shared with me in Caracas that most of the nucleos begin their programs for children between the ages of 6 and 8, but that they hope to expand their programming to reach even younger children.

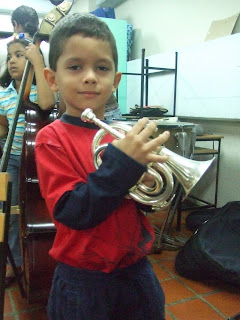

La Rinconada and Maracay are doing just that. These two nucleos are recognized for their early childhood programs, including classes for parents and toddlers. I also observed a Mozart Orchestra in Barquisimeto that had children playing brass and woodwind instruments as young as 4 years old! Like the miniature stringed instruments seen in most nucleos, Barquisimeto provides smaller brass instruments to fit the hands of these very young musicians. Even though you’ll see one or two students struggling with an instrument that’s just too big for them, it's been obvious to us throughout our travels that the nucleos are dedicated to meeting children where they are.

Before sharing a 3-minute movie clip highlighting the early childhood instrumental programs at La Rinconada, Barquisimeto and Maracay, I wanted to share a few observations:

Human Values: Cesar Rangel, the President of OSA (Orquesta Sinfonica de Aragua) shared this: "The magic of the system is human values. The orchestra provides that." The early musicianship classes focus on these values. Children learn to take turns, respect their instruments and care for their fellow classmates.

Child-Size Instruments: Although the general rule across El Sistema for wind instruments is to wait until the child's permanent teeth come in, we saw children as young as 4 and 5 years old in Barquisimeto playing these instruments, miniature-sized. When asked how teachers deal with the "missing teeth" problem, the answer is: wait until the process is complete and then start up again. The recorder still plays an introductory role for wind instruments, as well as helps develop pitch discrimination for all of its young musicians.

Paper Orchestra Debate: Many of the teachers in the nucleos of both states of Lara and Aragua have not heard of the Paper Orchestra concept. When we explained that in Caracas the Paper Orchestra is used as a pedagogical step before a child plays an instrument (see La Rinconada posting for more details), one of the violin teachers in Maracay responded, " El Sistema is about getting instruments into the hands of children at an early age." She felt that a paper instrument might confuse the child, rather than help prepare them. Interesting contrast. So far, Caracas is the only place where we've seen the Paper Orchestra.

Solfege and Singing: In an earlier post, I shared that the nucleos we've visited view singing as an important precursor to playing an instrument because it helps develop the ear. Singing and solfege continue to play a key role in the early orchestras as well. When practicing a melody or rhythmic pattern on their instruments, these younger classes alternate between singing lyrics, solfege and playing their instrument.

Parent Investment: Many of the baby classes have parents learning right alongside their child or participating in a parents only orchestra or chorus class. These classes have a specific purpose: to strengthen support at home for the child's musical development.

Student/Teacher Ratio: El Sistema's core value of investing early couldn't be more evident in their student-teacher ratio. Wherever we go, these young orchestras have on average a teacher or teaching assistant for every six children! Nucleos also invest in their young adults by giving them teaching roles and responsibilities. Becoming a teacher is a much sought after goal by these young musicians and considered quite an honor.